Hans Rosling said how can you solve major challenges if you don’t understand the facts. He was a Professor of International Health at the Karolinska Institute and Founder and Chairman of Gapminder Foundation. As a well known and influential speaker on global issues, he used to systematically ask 10 questions to his audience about the state of the world. To his dismay he found that no matter the intelligence of his audience their true understanding of the world fell well short of being even adequate. In fact, their overall scores were worse than what a chimpanzee would score with random picks. His final book, “Factfulness – Ten reasons we are wrong about the world – and why things are better than you think”, dealt specifically with this issue. He was on a mission to save people from their preconceived ideas.

This is the tenth and last blog of this World View series. This series came about as I felt that it was vital to be up to date with the current state of the world across a number of dimensions and develop an integrated world view of where we are and where need to be going. This series was the result of over 18 months of extensive research across a broad range of subjects learning from the works of Nobel prize winners, professors, researchers and well respected individuals. It also involved analysing different databases, reading research and using the power of the web to capture information, understanding and alternative perspectives. I have tried to look at our world in an integrated way and explore a range of perspectives and not just confirm cognitive biases I already had. It is safe to say that my view of where we are and what we need to do going forward at the global level is different from my initial thoughts. What is unchanged is that I remain optimistic. To be an effective leader going forward I believe having a grounded world view is essential. Building successful sustainable businesses cannot be done in isolation anymore.

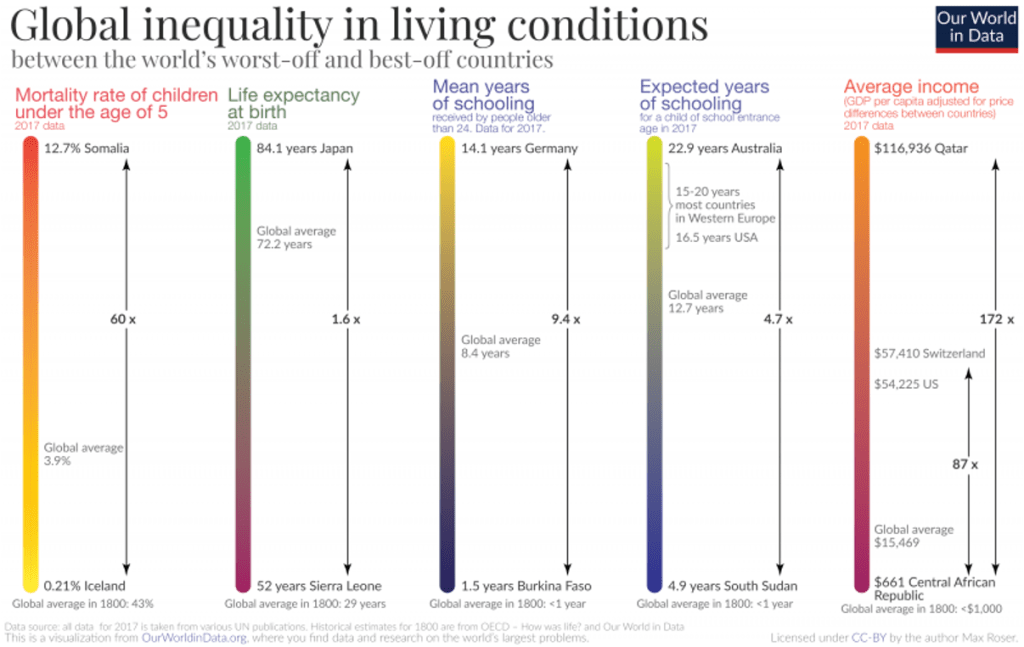

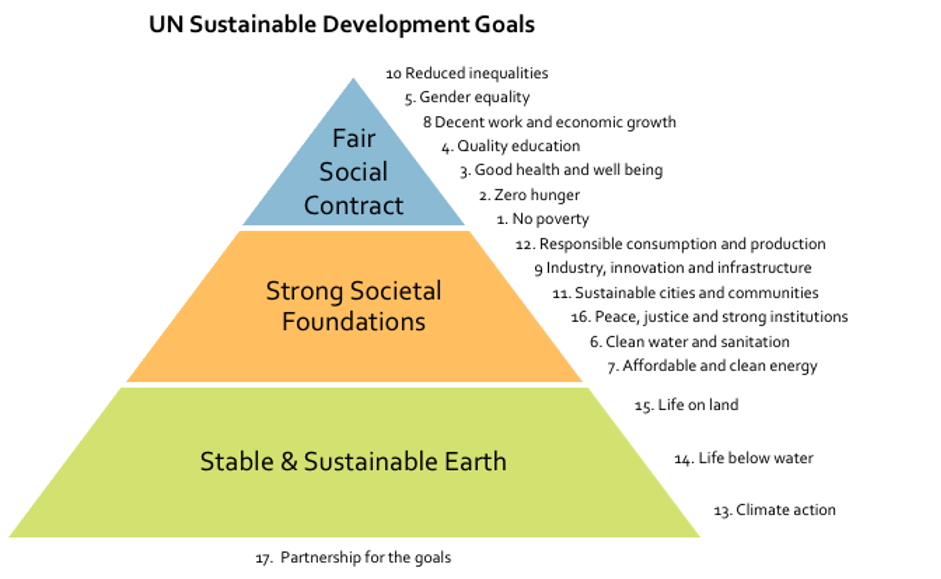

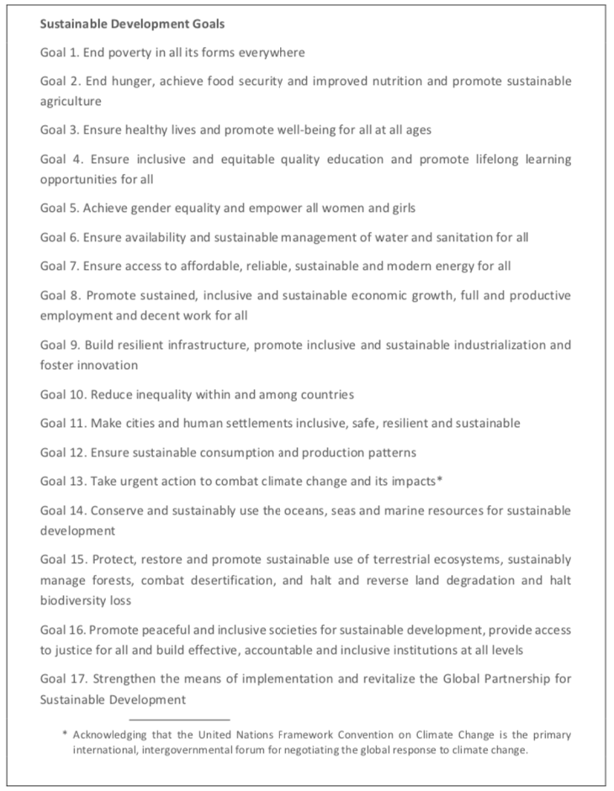

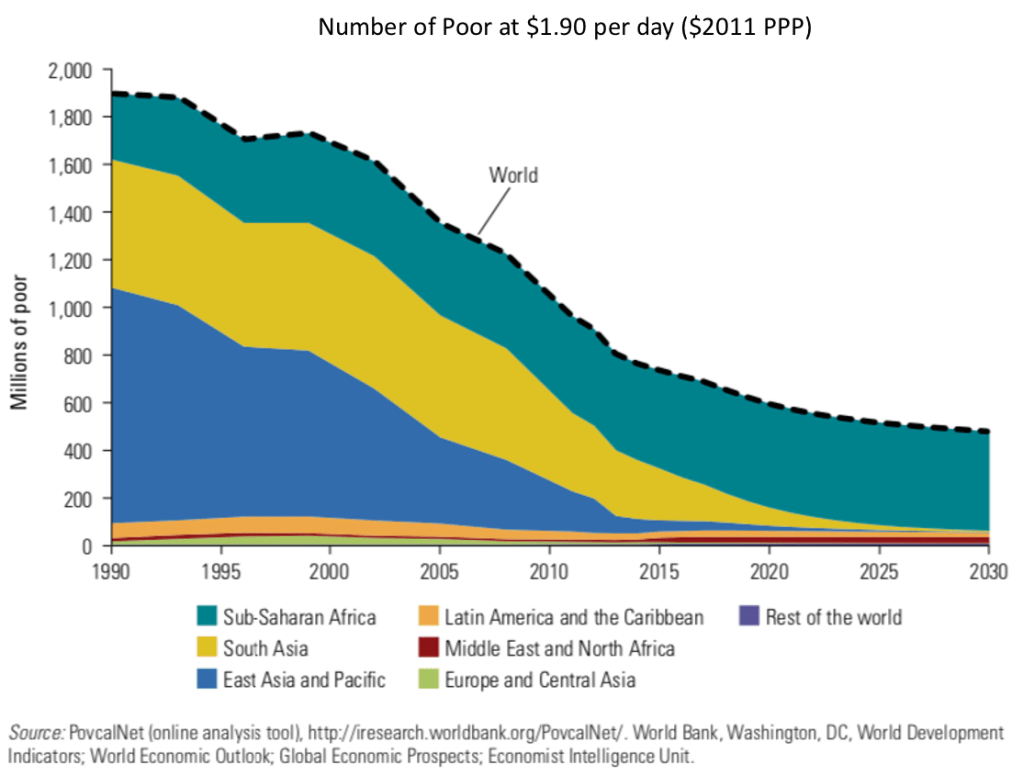

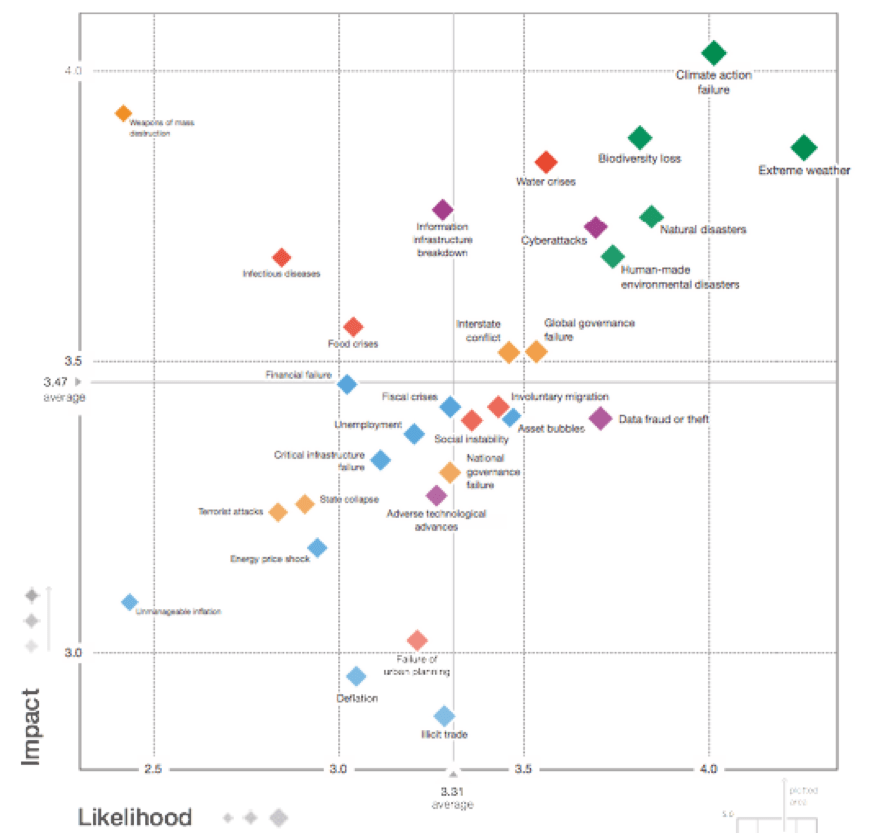

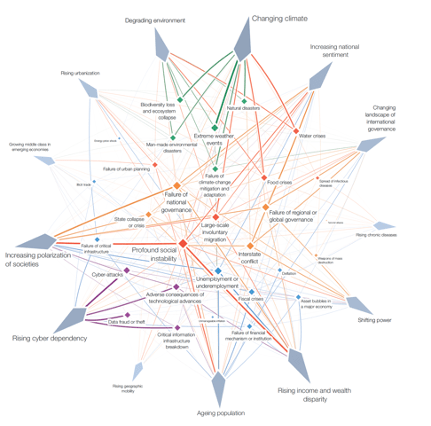

In the first blog, I laid out what I thought were the three big global challenges that needed to be addressed. Although being more tightly defined, not surprisingly they were consistent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the World Economic Forum Global Risk Report. The three challenges as I defined them were:

- Decarbonisation and Biodiversity Regeneration

- Inclusivity and Fairness

- Digital Privacy and Collective Truth

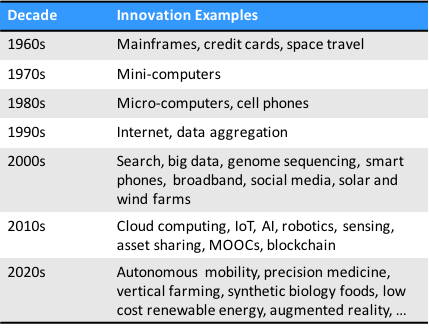

In the second blog, I analysed the components of successful societies. The third blog, set the scene for thinking about the challenges going forward in the context of what should be the social contract for citizens of a society. The next three blogs covered off different aspects of delivering against the social contract – democracy and the role of government, the market economy and capitalism, and the nine waves of technology innovation. Blogs 7 to 9 each explored in more detail one of the three challenges, including thoughts on how to solve them.

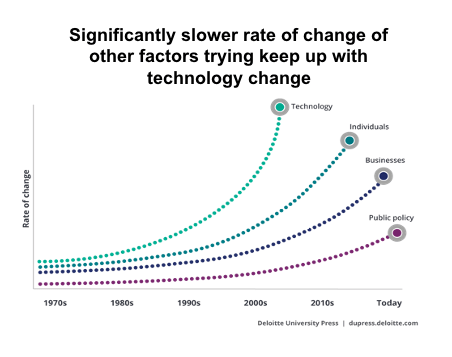

This tenth blog explores the keys to unblocking one of the most critical barrier to success, urgency and alignment. It is not a case of not understanding the challenges, shortcomings in our scientific knowledge, a lack of potential solutions; rather it is a lack of urgency and alignment that will make us fall short. And, don’t forget the consequences are immense! Together the challenges are solved by underpinning them with policies, incentives and appropriate stakeholder pressure provided on a timely basis. Given where we are, we know that the current governmental policies and the outcomes of our market economies and capitalism have been inadequate, and therefore, need to change. As Albert Einstein said, “The definition of insanity, is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting a different result”.

Getting the right balance of incentives, carrots and sticks, across participants that need to change is the biggest challenge. The shaping of them must take place from the supra-national level, to national/regional/local governments, to the private sector, the third sector and to the public itself.

In the last few weeks, we have seen some critical indicators that we are making progress on this topic of urgency at the governmental level. In late April, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court made a judgement on Germany’s 2019 Climate law which set as a target to cut 2030 carbon emissions by 55% from the level of 1990 and emit no net greenhouse gases by 2050. The Court ruled that the younger and future generations are entitled to “fundamental rights to a human future” and the current legislation results in a “radical burden” post 2030 on future generations that would drastically reduce their freedoms. The government now wants to lift the 2030 reduction target to 65%, and to bring forward the net carbon-neutral date to 2045. In a similar vein, in 2019 the Supreme Court of the Netherlands ordered the government to substantially increase its ambition after it watered down its carbon reduction target.

In Asia, there has been increasing legislation focused on digital censorship, including fake news, coming from a number of countries including Singapore, Malaysia, India and most recently Indonesia. Although, the focus includes dealing with the critical issues of national security, disturbance of public order and the conduct of elections; it can be said that much of the legislation is overreaching.

In the private sector, there is also progress. In a landmark climate case in late May 2021, the Dutch court ordered Shell to reduce its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 from 2019 levels. This is in comparison to their current targets of 20% by 2030. In the same week, a small activist hedgefund, Engine No. 1, managed to replace two existing board members at Exxon with its own candidates to drive the company towards a greener strategy; and, Chevron shareholders rebelled against the Company Board by voting 61% in favour of forcing the group to cut its carbon emissions. Investors are increasingly taking these challenges seriously.

The cornerstone for making this happen is at the country level where government policies, taxes and incentives set the tone for the kind of society that needs to be built. They need to raise expectations for the private sector, and more diligently think about the social contract which they have with their citizens.

Supporting this are supra-national pressures to get all countries on board with the overall goals of fighting climate change and environmental degradation, and inequality. The UN Climate Change Conference in November 2021, COP26, will be a critical indicator of the level and urgency of ambition to tackle climate change at both the governmental level and by the private sector. There is also the 76th Session of the UN General Assembly in September 2021 which will be looking at the progress against the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, ongoing pressure needs to be coming from the G7 and G20 conferences.

In addition, it is the involvement of financial markets, investors and asset managers that control the flow of funds to and from different sectors. The broad pressure points are coming from central banks, organisations such as Climate 100+ and ESG reporting requirements. Momentum is growing; however, the rate of change of aligning investment and financing decisions is too slow and the pressure for faster progress by the companies they are investing in is too light.

As long as boards and executive management are driven by short term strategies, thinking and incentives, change will be too slow. In large US corporates, changing the momentum from a continuously growing level of CEO compensation, from 30-40 times average worker compensation in the 1980’s to the current day level of 300-400 times, based on short term corporate performance to more challenging longterm performance with clear and ambitious impact goals is not in the self interest of these leaders. Boards must be willing to rapidly align the structure of compensation with long term sustainability. The Boards must be motivated to do this by the investors and asset managers; and where appropriate or needed by governmental policies, taxes and incentives. If leaders don’t adopt the need and urgency then nothing will happen. This is both a question of ensuring they are aligned with the priorities and they are leading with the right time horizons.

Finally, there are the citizens, who are also employees and customers, who need to use their voice and actions to drive change and must also change themselves. To do this they need transparency on the environmental and social behaviour of the company that is captured within the ESG reporting requirements. As noted earlier, both the court judgements and the shareholder actions were all triggered by stakeholder activism. More than ever stakeholders (employees, consumers, public, investors, etc.) are increasingly powerful voices that are requiring changes to corporate behaviour and a fundamental shift to responsible capitalism.

If you look at the private sector challenges, at its simplest level there are three dimensions to getting the incentives right and driving impact. Firstly, rewarding value and impact creators. Too much of our economy overly rewards value extractors, including profiting from trading and financial engineering, which adds little to the economy and nothing towards addressing these challenges. The question is, are you adding value and moving towards meeting the outcomes required by the challenges, or are you not contributing or falling short of the outcomes required. For any company or organization, if you have no measurable and relevant impact goals you should be seen as a value detractor regardless of what you are doing. Value creators should benefit in terms of governmental policies, tax levels and incentives in comparison to value detractors. Mariana Mazzucato, a leading economic thinker, has written a seminal book on this topic, “The Value of Everything – Making and Taking in the Global Economy”

Secondly, ensuring a proper balance of priorities across the short, medium and long term horizons. The challenges of climate change, biodiversity and inequality cannot be solved and be properly addressed in the short or medium term; however, investment in factors that have vital long term outcomes are required now. Achieving Net Zero for most companies and all countries will take more than 10 years; but, investment almost certainly needs to start now. Longterm investment behaviour should be rewarded vs. short term profit taking and extractive behaviour. Once again, policies, taxes and incentives are needed to assist in biasing investment returns towards impact focused investments.

Thirdly, addressing the challenges with the right urgency. This defines whether organisations own goals are in line with the timing of the needed/agreed collective achievement of the challenges.

To create urgency and alignment in incentives there are a few key principles. Firstly, the goals and related incentives need to be as simple as possible. Incentives must cover both value creation and impact in a balanced way. Secondly, the goals need to be clear, transparent, timely, measurable and auditable. Thirdly, programs and incentives must be adjustable to new and preferable technological solutions. Although overall long term targets are clear, interim targets and the set of actions to achieve them are not. Finally, incentive design must understand the heavy human bias towards focusing on easier short term goals and rewards vs. not comprising long term targets. It is a natural inclination to back end load change which often is beyond the work horizon of the existing leadership team. Early investment and impact gains are essential for success.

At the governmental level, it is vital that they set the tone in terms of level of ambition, timing and responsibilities. As I often say, uncertainty is the enemy of progress. Clear forward looking and stable policies, taxes and incentives will accelerate the commitment of investment by the private sector. These programs need to create alignment of the private sector with the goals and urgency of them; bias scale investment to meet these challenges; secure government financing to meet their own commitments; and, ensure the right research, development and innovation is happening to solve challenges where no economic solution currently exists.

Rightly so, there are concerns about overbearing and overly complex involvement of governments. However, it is also important to note that pure capitalism does not have a track record of solving these types of problems without the right involvement of governments. Policies, regulations, legislation, taxes and incentives need to set the direction towards outcomes and define the urgency; but not, specify the exact set of solutions. Marianne Mazzucato has defined this as “mission oriented” governmental programs. These activities should be designed to unleash the market power, speed and innovation capacity of the private sector to be the major contributor to the solution of these challenges.

In the second week June 2021, the senate broke their partisanship and agreed a mission oriented spending bill, the US Innovation and Competition Act, of a quarter of a trillion dollars focused on key technology sectors. This was achieved by defining it very much as a way the US can strengthen their competitive and adversarial position with China in key sectors. China has successfully had mission oriented programs to achieve leadership in specific technology sectors, including areas such as solar and electric cars.

So much can be achieved by just putting these frameworks in place, and then allowing innovation, financing and entrepreneurial energy to drive change towards the goals in the most effective way.

Without solving alignment and the creation of appropriate incentives using both carrots and sticks, it is highly unlikely that these challenges can be met on a timely basis.

I hope this series has been insightful to help you build your own World View. In this rapidly changing world, politically, economically and technologically staying abreast of where we are and what is possible is vital for leaders. There are also increasing requirements and expectations in terms of responsibility to have an impact on the key environmental and societal challenges. The need for boards and executives to be on top of the context in which they operate will be an essential component of long term sustainable success. Our collective success and sustainability will be linked to solving the three challenges of Decarbonisation and Biodiversity Regeneration, Inclusivity and Fairness, and Digital Privacy and Collective Truth.