Blog 5 of Business Strategy Series

In Blog 4, I completed the brief discussion on the current global environment.

To summarise the key points I made in Blogs 2 to 4, the thread of the story was as follows:

- Covid 19 exposes how little we are prepared for serious disruptive events

- We live in a complex world with many interconnected factors that will affect our businesses

- There are multiple types of events that can occur over time that can be highly disruptive to businesses

- We must move from thinking businesses operate distinctly from the global ecosystem and should only be profit focused.

- Businesses need to be part of the global ecosystem, and will be mandated to look this way, so strategy must be looked at from a system perspective.

- The perspective of how we fit into a sustainable world is best reflected by the global consensus represented by the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The nested circles below (Figure 5-1) illustrate that a business needs to not only build on their identified business opportunity but it must do so in a way that is aligned with the sustainability requirements from an economic, social and environmental perspective.

There are eight gaps in conventional strategic analysis and thinking that need to be integrated into system based business strategy. The next set of blogs are going to these eight gaps that are critical to strategic thinking going forward. The eight gaps are:

- From shareholders to stakeholders

- From Michael Porter’s five forces to macro models

- From risk monitoring to business resilience

- From product-market fit to customer-product fit

- From simple to multi-factor business models

- From product to company technology, innovation and design

- From profit focus to triple bottom line

- From medium term strategies to long term scenario based strategies

The place to start is ‘from shareholders to stakeholders’. Some of the early thinking on shareholders, was discussed by the well known economist Milton Friedman. In his 1962 book ‘Capitalism and Freedom”, he stated, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game”. This was linked to his view that the sole responsibility of management was to its shareholders.

This Friedman doctrine, has been the driving force of thinking and management behaviour ever since. Businesses are run with an intense primary focus on a mix of profitability, growth, and return on investment which are the critical drivers of shareholder wealth creation. We see this every day in the stock markets and is the pervasive thinking in private equity. If you look at the standard structures of incentives for CEOs and their management team, the core wealth generators for them are linked to financial performance and share price performance. This is coupled with the view that stock markets are focused on quarterly performance.

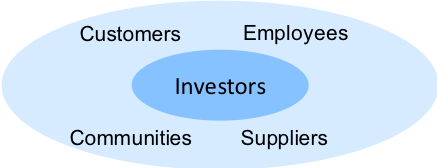

As the world has moved towards and into the 21st century, there has been a growing shift to increasing the view of stakeholders beyond investors to include other direct stakeholders (Figure 5-2).

This broader definition of stakeholders has to a large extent been at the core of many ‘family’ owned companies that have been around for decades. It has also been a much more important part of the thinking of the companies situated in the EU and certain Asian countries. The reality of these other direct stakeholders is that stronger relationships with each of them will create stronger and more sustainable economic performance. Alienating employees, not treating customers well to build customer retention, and having unstable relationships with suppliers tends to create financial and operating performance issues over time. In a number of countries including Norway, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands, company boards reflect the importance of a broader set of stakeholders by having specific representatives for the employees, unlike countries such as the US, Canada and the UK.

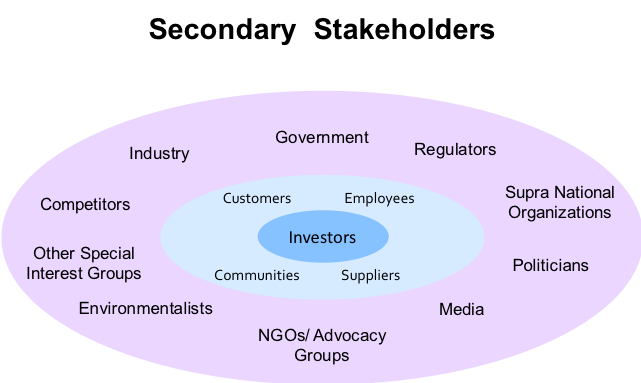

Through experience over the years, and as market and consumer behaviour has been changing, it has started to become clear to businesses that there is also a secondary set of stakeholders (Figure 5-3) that can also have a direct impact on the well being of a company and need consideration.

These impacts can come from a range of different groups and involve impacts such as regulatory challenges, acquisitions being blocked, government fines or additional taxes, and brand and reputation damaging press from advocacy groups or the media. Clearly, strong relationships with these stakeholders can also have the opposite effects and open doors to opportunities.

Here are some examples that many of you will be aware of and I am sure there are many other examples that come to mind.

In May 2017, Facebook (Figure 5-4) received an EU $122m fine for the breach of anti-trust regulations, and then in 2018 the EU started an action against Facebook for privacy breaches which had a potential fine of $1.6bn. In 2019, the Federal Trade Commission imposed a $5bn fine for violating consumer privacy. As well as the fine, the settlement order also required Facebook to restructure its approach to privacy from the corporate board level down, to establish strong new mechanisms to ensure that Facebook executives are accountable for the decisions they make about privacy, and that those decisions are subject to meaningful oversight.

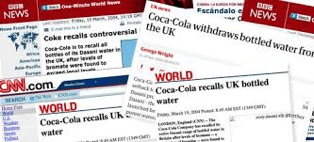

In 2004 Coca-Cola (Figure 5-5) launched Dasani, a leading bottled water brand in the US based on tap water, into the UK. The use of tap water and an ‘interesting’ marketing campaign caused a negative media frenzy, and then a Coca-Cola headquarters frenzy, and resulted in Dasani having to be withdrawn from the UK Market and cancelling planned launches of Dasani in certain other regions of Europe. I will let you search this incident on the web if you have time for the more detailed and amusing story.

The Volkswagen emissions scandal (Figure 5-6) began in September 2015 linked to a violation of the Clean Air act in the US. This breach resulted in plans to spend €16.2bn in reparations and a $2.8 bn fine (source: Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volkswagen_emissions_scandal). Another example of the failure to meet regulatory compliance and the need to be on top of all regulations and potential new regulations.

We are all aware of the environmental movement (Figure 5-7) and the impact it is having on many companies resulting in damaged brands and reputations, boycotting, or brand switching to more ethical brands. A lot of this pressure has come from a combination of activist groups, such as Greenpeace, naming and shaming companies involved in areas such as deforestation of the Amazon, and public protests including the activities of Greta Thunberg.

Understanding the relevance of these different stakeholder groups is an essential component of strategy. Evaluating the power, risk, legitimacy and urgency of these stakeholder groups will affect strategies, priorities, investment spend and programs for effective management of the key groups.

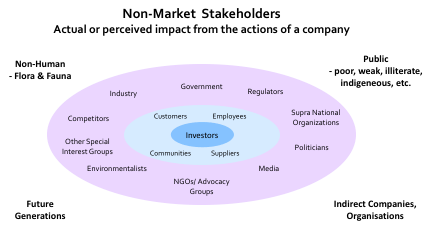

Fully understanding stakeholders, does not end with incorporating secondary stakeholders into your thinking. There are non-market stakeholders (Figure 5-8) who are outside of the market of the company but can be indirectly deeply affected and therefore affect the company in return.

As can be seen in Figure 5-9, these are examples of the types of corporate related activities that have had significant effects on non-market stakeholders. There could be future generations that have severe health and well being problems as a result of nuclear or chemical disasters, or poor and indigenous groups that had been taken advantage of but now have rights. It could be severe economic damage to indirect businesses, such as in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill involving BP. By 2018, it was estimated that this had cost BP $65 bn, including $4.5bn in fines. Finally, with the environmental movement, damage to Flora and Fauna could also have consequences for a company.

We have outgrown, Milton Friedman’s view that the sole objective of a company was to increase its profits within the rules of the game. He argued that the appropriate agents of social causes are individuals—”The stockholders or the customers or the employees could separately spend their own money on the particular action if they wished to do so.” Today, charity does not solve the concerns of the secondary and non-market shareholders! Thoughtful strategic integration of the needs of legitimate and valuable stakeholders is essential. Effective management of all material stakeholders needs to be a fundamental part of managing a business. In relation to climate change and the environment, we are already seeing that companies not focused on sustainability are losing access to finance, having trouble attracting and retaining talent, and losing customers. We are only in the early stages of this movement!!

In summary, the landscape of stakeholders is broad and complex and their potential impact on businesses is continually evolving and changing. Organisations not understanding this will have strategic and performance shortcomings, and be remiss in their responsibilities.