It is difficult to understand what was truly achieved at COP 26. After pre-weeks of media to COP 26 and then the concerted media campaign during the week of COP 26 how do we sort the wheat from the chaff or the greenwashing from the truth.

Fundamentally, there is still a long, long way to go. COP 26 was not the breakthrough that was needed. Both the public and private sectors did not step up and demonstrate the urgency that was needed.

Here are my 10 key thoughts:

1. COP 26 was more than blah, blah, blah, as Greta Thunberg said; but, it fell far short of what was needed. It was inevitable that we would fall short of 1.5 degrees Celsius, the question was really how far? The best guess seems to be that the commitments added up to about a 0.3 degree Celsius improvement moving our current likely outcome tracking from +2.7 Celsius warming at 2050 to 2.4 degrees (per Climate Analytics Tracker or CAT). In Climate Actions latest publication, they noted that not only do the commitments fall short of the +1.5C target of the Paris Climate Agreement, there is no single country that has put short term policies in place to put itself on track to its net zero target.

2. Out of Glasgow, there is recognition that this push to improve commitments cannot just happen every 5 years. This is a good move. They are now asking countries to each year look at ratcheting up their targets and actions. For most countries, setting 2030 targets rather than earlier targets is also a way to delay the need to address the problem to the next leadership group whether in the political or private sector arena. Given that the carbon emissions problem is a cumulative problem there should be a further goal of each country committing to a set of annual activities and targets; and, couple this with ‘naming and shaming’ of those that fall short. Ramping up public pressure is fundamental to proper progress.

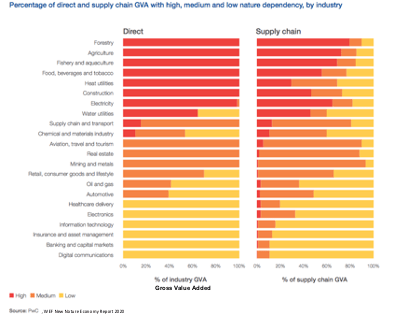

3. COP 26 recognised that it is vital to solve the biodiversity issue as part of the climate problem even though it has a set of other issues. The reduction of deforestation pledge by 118 countries by 2030 is a start in the right direction. This should be enacted much faster. Nine more years of deforestation is a problem. The devil will be in the detail of the agreement; including, the addressing of illegal logging and the need for reforestation. The three regions of particular concern are the Amazon, the rainforests of Indonesia and the Congo Basin.

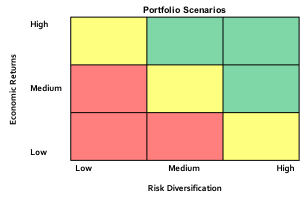

4. The announcement of GFANZ (Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zer0) having 450 organisations that manage $130tn of private wealth saying they will participate in the financing of the climate challenges is a good start. Mark Carney has made good progress to pull this together. The cynic would say that if there was $100tn of investment opportunities (the size of the climate challenge) that will add 2% per annum of economic growth and they were presented as good investment opportunities who wouldn’t want to be part of the club. The key question is in reality will this result in large scale material changes in investment allocations and what will it also take to make this happen in terms of reporting, policy and regulatory changes, carbon tax, last mile of risk security, etc. The reality is this is a step in the right direction; but, there is a long way to go.

5. COP 26 forgot the oceans which is the biggest carbon sink. Where is the equivalent pledge to deforestation for the Oceans. What never seems to be included in the Net Zero discussion is that the goals required do not consider any indirect impacts of carbon emissions (including other GHCs) that are in carbon sinks on land and in the oceans. Only a very small percentage of GHCs are in the air vs. absorbed in the land and oceans and their biodiversity. The melting of ice and permafrost, the warming and acidification of oceans, and the equivalent of ocean deforestation from over fishing are likely to release GHC’s into the air. There are also other indirect sources of warming that have also not been considered.

6. COP 26 needs to get away from the sole narrative of clean energy and focus on the reality of a practical transition to clean energy. The coal and methane pledges are helpful but are really subsets of existing pledges that should already have been made or identified in terms of carbon emissions reduction to meet the 2030 targets that each country committed to. Countries should be solving not just the optimal future state of energy provision but also the economics of transition vs. the related cumulative impact of emissions. Optimal transition will require continued fossil fuel extractions (hopefully focused on the least climate damaging approach), being realistic on the ideal role of nuclear power and other credible low emission sources, and ensuring there aren’t economically disruptive shortages on the way. Governments have a big role to play in this in terms of creating the right economics of alternative energies (through carbon taxes, subsidies, other policies) and their own commitments to ensuring the appropriate energy grids are in place to maintain steady supply.

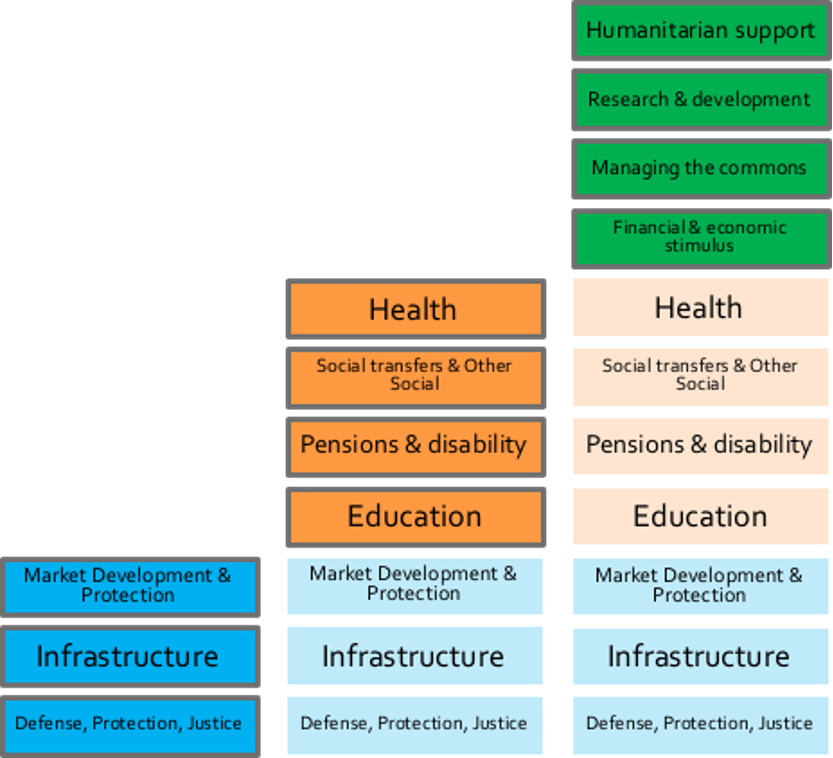

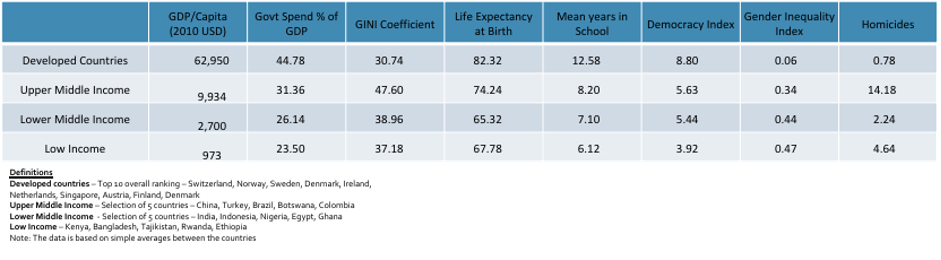

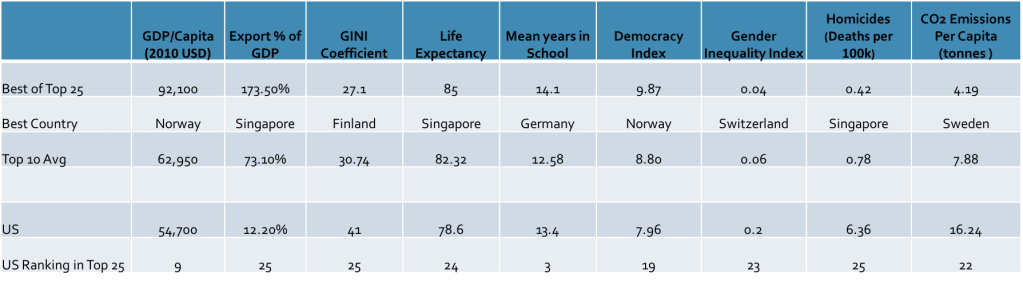

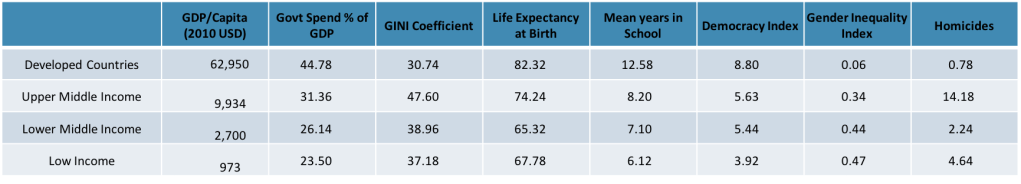

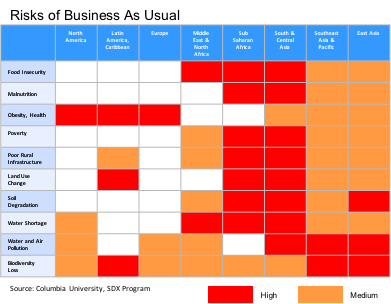

7. We still need more discussion on adaptation not just carbon emissions reductions. It has been good to hear that there are now some more realistic discussions on climate that are appropriately also talking about adaptation. The short to medium term economic benefits of dealing with climate change come from adaptation while the longer term benefits are from reaching Net Zero. Developing and underdeveloped countries are primarily concerned about adaptation to deal with the economic consequences of extreme weather. The first things they need are economic assistance to social and economic development to help deal with the ravages of droughts, increased heat, floods, etc. resulting from climate change. These include factors such as access to water, crops which are more resistant to the new climate reality they are facing, and access to 24/7 low cost energy ( and ideally low emission energy) for development. Given that a significant proportion of those in extreme poverty are subsistence farmers specific targeting of assistance programs will be essential.

8. Carbon tax hesitancy. It could be argued that the one thing that would indicate how governments are taking climate change seriously would be the agreement of a global carbon tax, or cap and trade, system. This also includes dealing with addressing the issue of heavy subsidies on fossil fuels in many countries including the United States. The shifting of the relative economics of alternative energies is vital to accelerating the investment in and adoption of new energy consumption habits. There has been no apparent progress on a global carbon tax program.

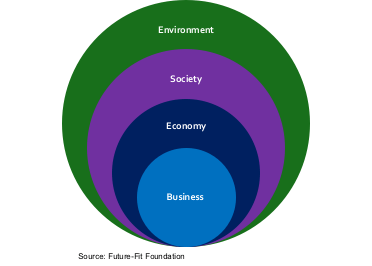

9. Global North and Global South was not properly recognised in COP 26. In the climate conferences, the Global North refers to developed countries; and the Global South are the developing and underdeveloped countries. The Global North completely dominates both the emission of GHCs and the use of fossil fuels. The global south has a small fraction of per capita consumption of energy; although, they do contain the large and growing proportions of the population. These countries have primary priorities on social and economic development which involves growth in energy consumption before achieving net zero is even considered. Very different programs of climate action should be targeted for common clusters of countries; rather than the chasing of universal agreement on a common set of actions. Why do we keep chasing all countries to sign up to the same agreements?

10. The increased level of stakeholder activism and engagement needed to drive change was not properly incorporated into the conference. There needs to be a much higher level of activism by stakeholders to drive change and hold politicians and private sector leaders accountable. The activism needs to include the public voting out of politicians, the boycotting of companies and withdrawal of funds from irresponsible companies by investors and insurers. In the same way that there needs to be activism there also needs to be proactive engagement of stakeholders in changing their own behaviours with respect to both the shift to Net Zero and addressing adaptation requirements. This means that every individual, town, municipality, city, province, country and region, as well as every other organisation in any form, has the simple requirement of acting themselves. This was completely missed at COP 26 as they tried to focus on newsworthy narratives vs. practical solutions.

As an optimist, I do think that we have the wherewithal to succeed. To do this we need to face the truth, deal with reality, and stop greenwashing problems and challenges. Transparency is essential, programs must be put on the ground and managed to time, results must be monitored, and actions must be taken against shortcomings.