Inclusivity and fairness is the second of the three challenges identified. The previous blog covered the first challenge, “decarbonisation and biodiversity regeneration’. The next blog will cover the third challenge of ‘digital privacy and collective truth’.

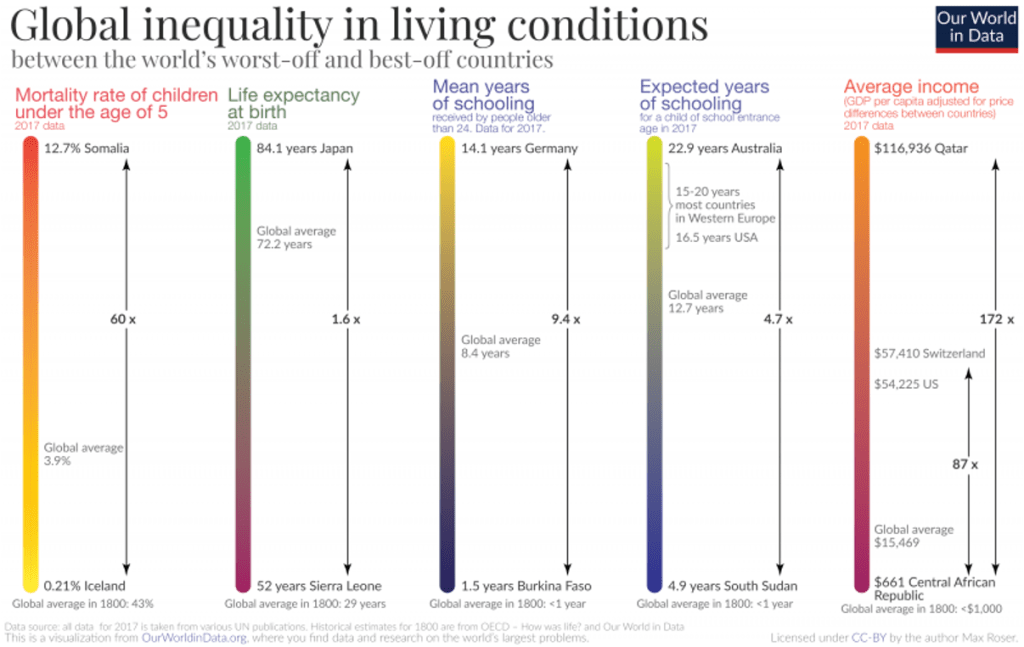

Can you imagine having a life expectancy of 52 years, 1.5 years of schooling and an average income of $661 per year? And for your children, looking at a 12.7% mortality rate under the age of 5 and only 4.9 years of expected schooling. In addition, you may have no shelter, you are undernourished, no clean water and virtual no access to health services. Is it any consolation that you are better off than the average person in 1800 on a number of dimensions? This is the worst of inequality – born in the wrong place on the wrong side of the street.

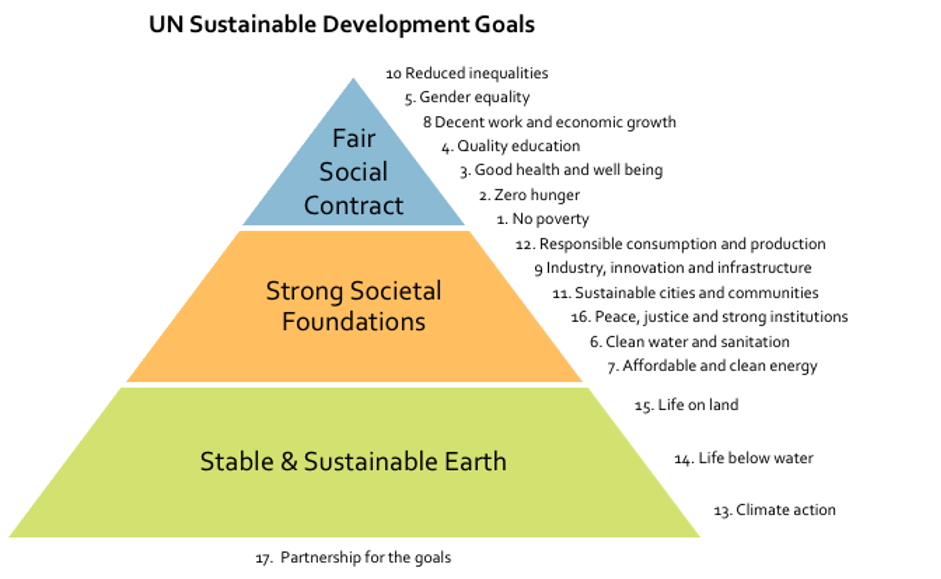

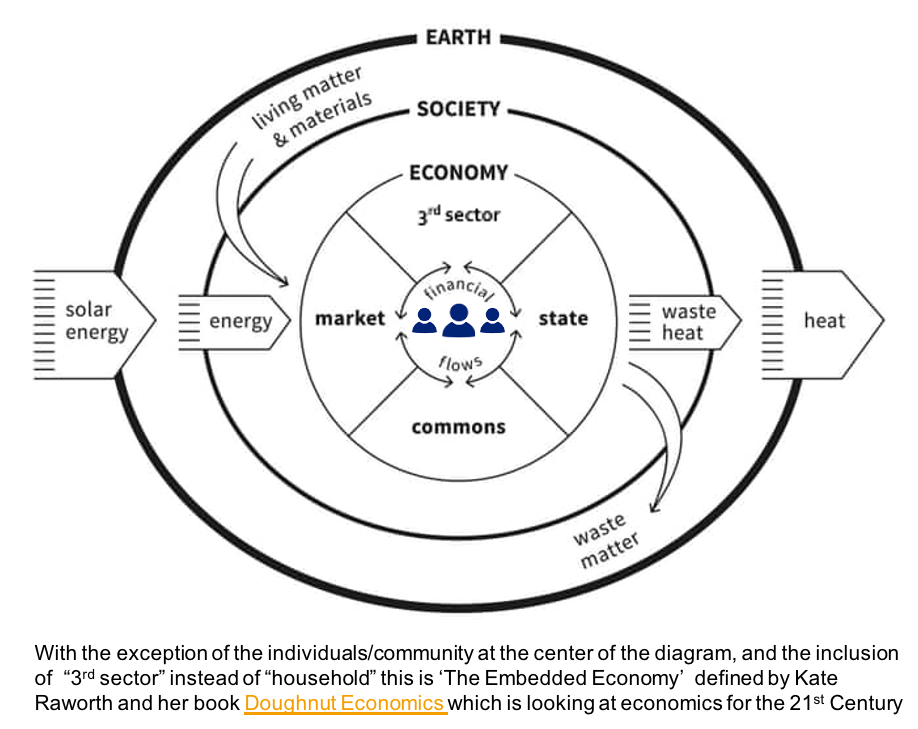

The climate crisis maybe the most existential crisis we have ever face but it does not stand-alone. Solving the challenges of inequality through a set of initiatives focused on inclusivity and fairness also need to be addressed. Probably, the best place to capture the overall goals that we need achieve are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 SDGs (Figure 8-1) which then had 169 sub goals. This is effectively the global consensus on priorities. Strong societal foundations and a fair social contract are critical components of the SDGs.

Why is it that we need to talk about inequality now after all the developments in the last 50 years? We have the technologies and the capacities to solve these issues and as I have noted before almost all the trend lines of progress have been going in the right direction with the major exceptions of income and wealth inequality.

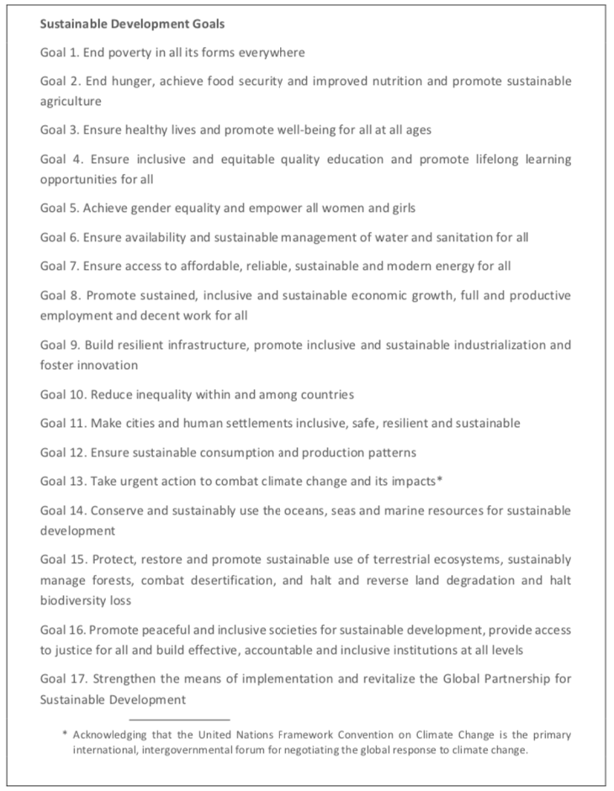

Just looking at extreme poverty, the reduction in the number of poor has been incredible since 1990 (Figure 8-2). The number of people in extreme poverty have dropped from 1,895m to 736m in 2015 and is now below 10% of the population from 36% of the population in 1990. However, looking behind the numbers we can see that this has been primarily a story of China; and, more recently India has also been making progress. In fact when you move from extreme poverty of $1.90 ($2011 ppp) per day to lesser levels of $3.20/day and $5.50/day China is also making significant progress. The region of most concern is sub-Saharan Africa where across all poverty levels noted above, the number of people is growing dramatically in this high population growth region. In fact, at $5.50 /day there are 895m people in the region in poverty. So overall, trends are not expected to continue and solve the problem of poverty. Additional interventions are required.

The core issue as I mentioned in the previous blog is the lack of commitment and pace to solving these issues and the hope that if we just keep on moving forward, as we have been doing in the past, the problems will go away.

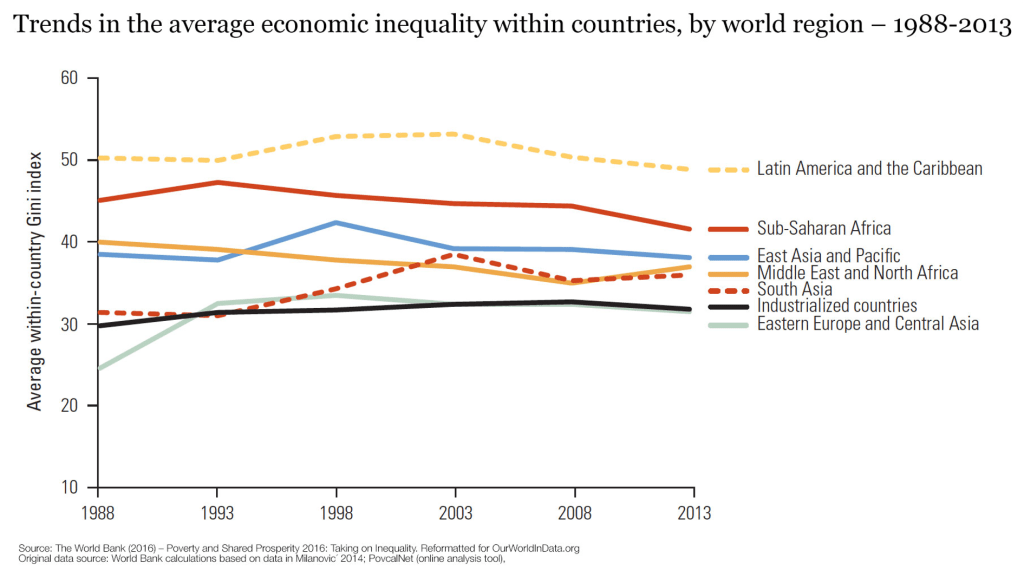

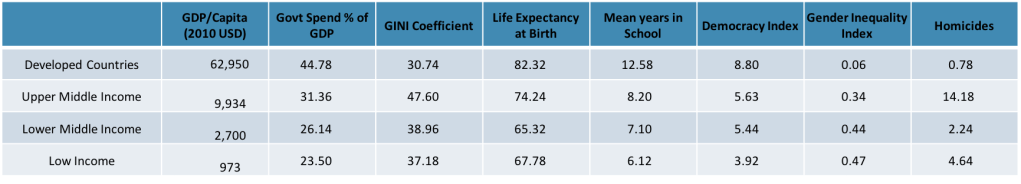

Inequality manifests itself in the context of extremes in distribution of income and wealth and the shortfall in access to the basic necessities of life – food, clean water, energy, shelter, clothing, health, education and technology access. We see the reality of these inequalities in different forms whether in sub-Saharan Africa, China or the US. Today, 71 percent of the global population live in countries where inequality has grown. In 2018, the 26 richest people in the world held the equivalent wealth of 3.8bn of the poorest people, half of the global population. Since 1990, inequality has increased in most developed countries and a number of middle income countries including China and India.

It is important to note that although there are growing levels of inequality within countries, particularly developed countries, the bigger source of inequality is across countries. This is contrary to the source of inequality 200 years ago when 80% of inequality was found within countries as opposed to 20% today.

| Class Inequality (within a country) | Location Based Inequality(across countries) | |

| 1820 | 80% | 20% |

| Mid 20th Century | 20% | 80% |

With growth in incomes in the developing world exceeding those of the developed world there has been some narrowing of the inequality gaps between countries especially in Asia and parts of South America; however, there has been little progress across sub-Saharan Africa.

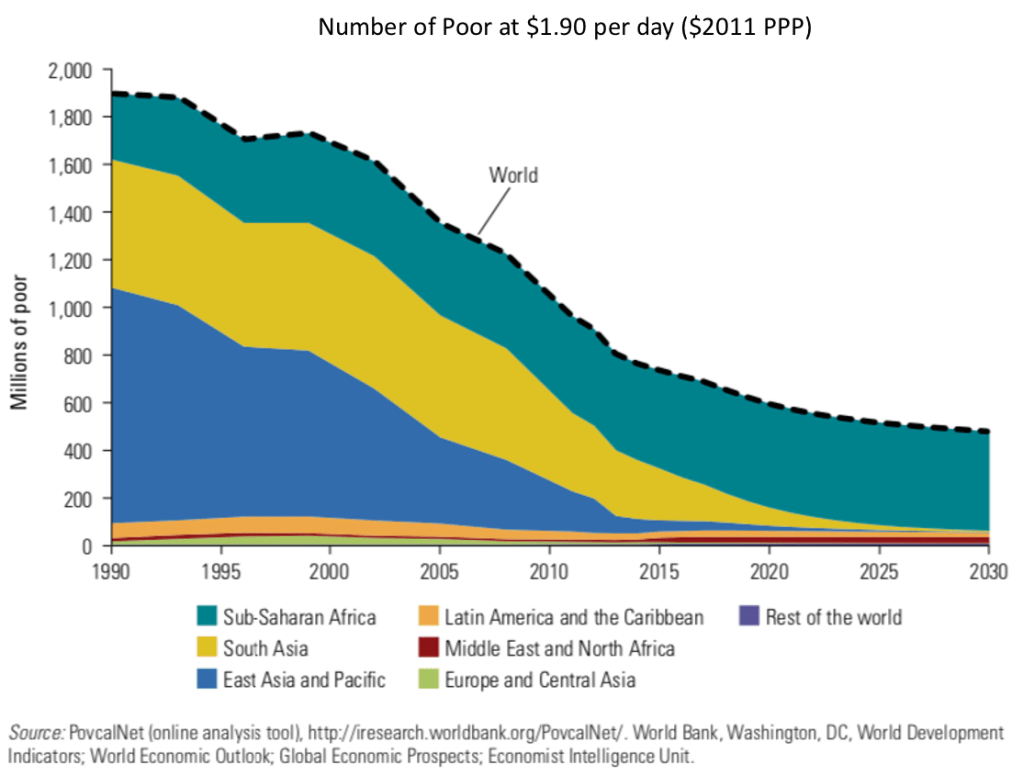

Traditionally, there has been the belief that inequality over time follows Kuznets Curve (Figure 8-3). Kuznets Curve argued that income inequality tends to increase at an initial stage of development and then decrease as the economy develops, implying that income inequality will fall as income continues to rise in developing countries.

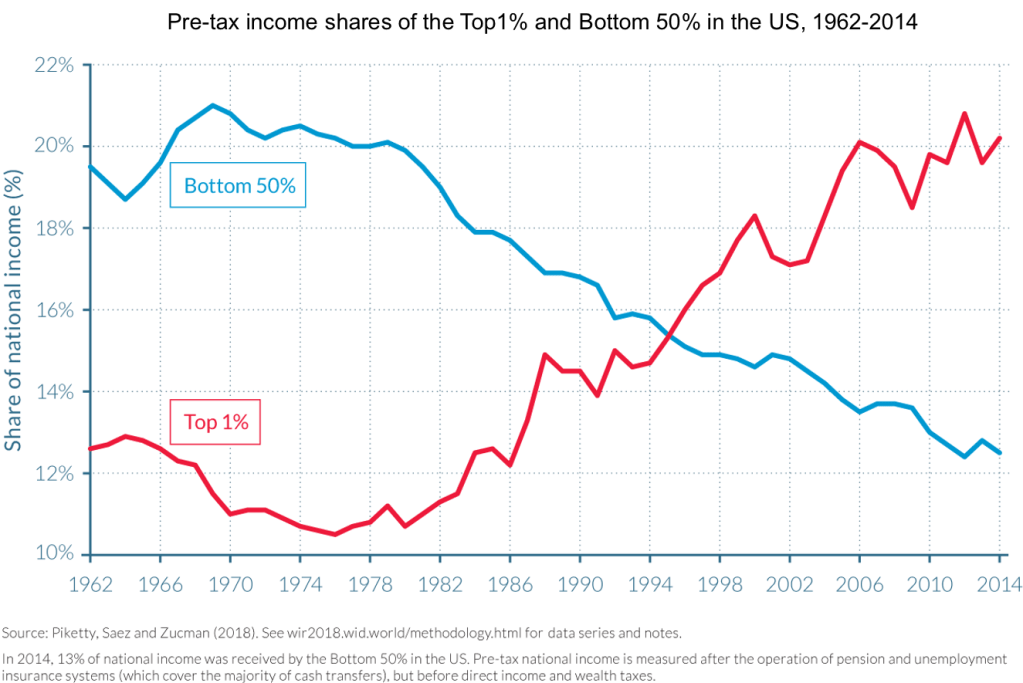

Conceptually, this curve appears to make sense; yet, it does not appear to happen in reality (figure 8-4). In the upward sloping part of the curve, the shape depends on where the developing country was starting from. In the case of China with communism, they started from a low level of income inequality (low GINI score) and the income inequality has risen; however, in South America many countries started with very high GINI scores, perhaps linked to their previous colonial situations, and the levels of inequality have been slowly declining since about 2000.The downward shaped curve for developed countries does not also bear truth. In the Western world, this did appear to be possible until about 1980 when the curves started to rise again for key countries such as the US, some countries in Europe and overall, in particular, in the English speaking countries. The down-curve only appears to happen when there are appropriate progressive taxes on income, when tax rates on wealth are not less than taxes on income, and the income growth rate exceeds the average return on capital.

In countries, such as the US, which are now more resemblant of plutocracies than democracies these conditions are not being met and therefore inequality will continue to grow. In the US, tax cuts are primarily for the top 10%, and especially the top 1%, who benefit from lower income tax rates and lower capital gains tax rates. As an example, the wealthiest 400 families in America in 1960 paid as high as 56% in taxes, by 1980 it was 40% and in 2018 it was 23%. The bottom 50% of households in America in 2018 paid an average rate of 24.2%. Figure 8-5 shows the increasing concentration of income in the US mirroring the declining share of the bottom 50%. In terms of wealth, in the US the top 1% have over 40% of total wealth and the top 10% comprise about 80% of all wealth. Both of these percentages of wealth are continuing to grow.

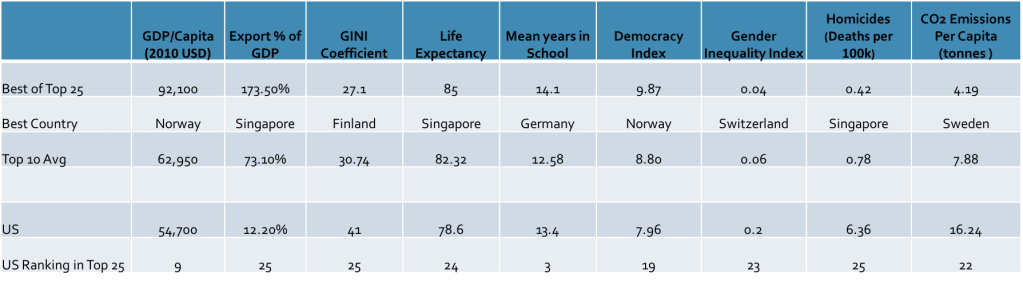

We have not seen this disturbing trend in many of the successful countries in Europe where across all dimensions their levels of inequality, or lack of inclusivity, are much lower; and, their average GDP/capita is higher than the US.

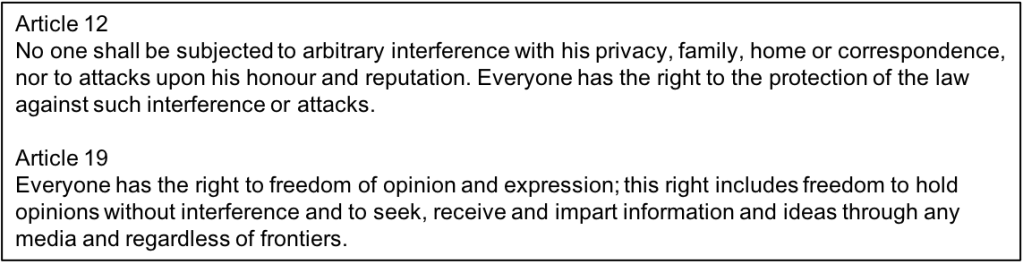

Inequality is also reflected in freedoms, access to opportunities and economic mobility, and the rights of safety, security and equal justice. We see these issues every day in the news whether it is about the Uighurs in China, the Rohingya in Myanmar, Black Lives Matter in the US, the unequal treatment of women and girls in Afghanistan, the Middle East and most other countries.

Growing inequality and mistreatment of groups of people builds political instability and is the antithesis of what is required of building a strong and stable society. The historic metrics have been focused on watching the growth in averages. Growing average income, average expected life, average years of education is only good in a society if the growth has some form of distribution. If most of the benefit goes to the top 10% of society and none reaches the bottom 50% then the average is misleading. What is needed is a focus on inclusiveness where no one is left behind.

This is not about being driven by minority interests, it is about practically being inclusive. It is the practice or policy of providing equal access to opportunities and resources for people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized, such as those economically disadvantaged, having physical or mental disabilities, or belonging to disadvantaged minority groups.

Inclusivity and fairness is about ensuring that of primacy there are minimum standards and principles that countries need to focus on. This is about not being left behind and it is about having a minimum set of opportunities for a good life at birth. It is about minimising the differences in access and treatment across the basic requirements of a strong functioning society including equalising the access to quality education, equivalent outcomes for healthcare (eg. life expectancy), and equal opportunity. It is about ensuring that we are addressing the unacceptable and then moving forward. The definition of these items are not my views, they are those articulated within the UN SDGs. The SDGs articulate where we need to get to nationally, regionally and globally.

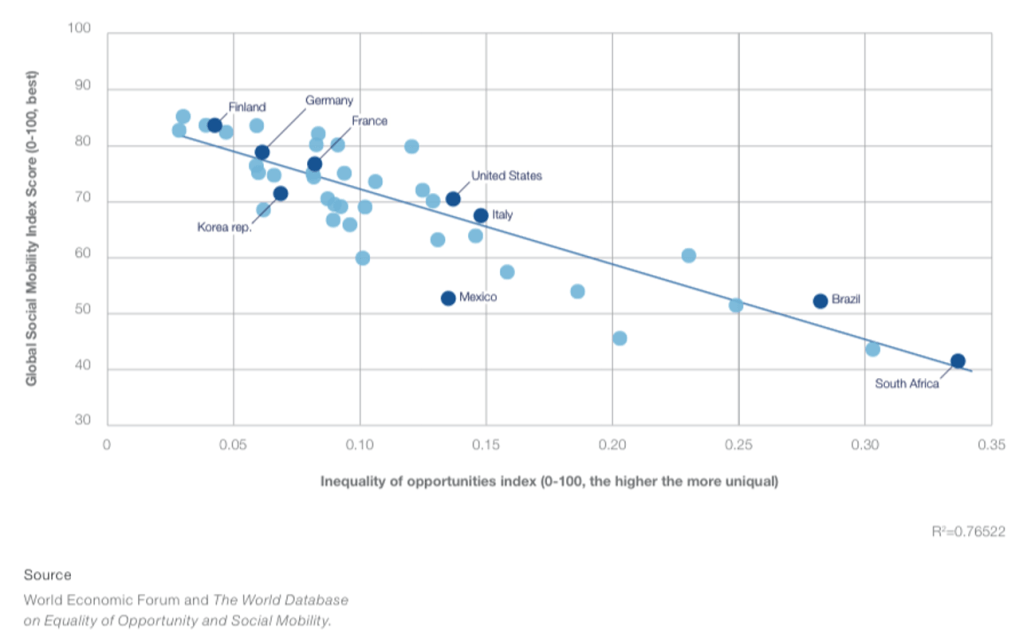

The outcome of inclusiveness and fairness should be social mobility. As can be seen in Figure 8-6, there is a strong relationship between inequality of opportunity and global social mobility.

In the World Economic Forum’s new Global Social Mobility Index, 17 of the top socially mobile societies are in Europe with Denmark being the overall leader. The US is 27th, while China is 45th and India is 76th. In Figure 8-7, you can see how the US ranks across the different mobility factors. The set of factors illustrated shows just some of the complexity of what needs to be addressed.

An important context to the solutions is to also address potential negative impacts from changes in how society is developing. There are five critical dynamics to consider. Firstly, changes in the nature of globalisation affects both where companies are sourcing their labour and where demand will be generated. We have seen recently with the Covid 19 crisis and increasing geo-political tensions that the dynamics are changing. There is also the inevitable shift in economic power towards China and ultimately India away from the US and Europe.

Secondly, the impact of technology on labour markets. Technology and innovation are increasing the interchangeability of labour and capital. The innovative use of robotics, AI and autonomous vehicles will have profound effects on labour markets. This will cause the need for more comprehensive social security programs and the need for increased levels of continuing education to improve labour mobility. Without addressing this, there will be further pressures on the decline of the middle class.

Thirdly, the propensity for increased concentration of income and wealth within countries. Unless countries address the increasing concentration of income, wealth and power, increasing social unrest is inevitable. The importance of the use of both progressive taxes and taxes on wealth is an essential component to addressing this problem. This will also provide critical financing for deeper programs to address inclusivity and fairness.

Fourthly, the changing composition of populations within countries. In the last 40 years, there has been dramatic changes in the composition of populations within countries. The mixes between pre-work, working, and retired populations have changed dramatically. In particular, in the developed world solving for managing in situations where the retired population is a major part of the mix of a country raises real challenges. Post 2050, other than sub-Saharan Africa virtually all other countries will have peaked in populations and will be ageing.

Finally, climate and environmental crisis. All the evidence points to the developing world, especially sub-Saharan Africa and India, being particularly affected by increased temperatures, which impacts food production and water access. In addition, we know that the increase in droughts, floods, fires, etc. will impact the most disadvantaged.

Moving towards a more inclusive and fair world with base standards of living, freedoms and opportunity can be broken down into 2 areas to address. Firstly, in-country inclusiveness which is about thinking about the problem within a country at the individual level. Secondly, across country fairness is about policies and programs that are required to help underdeveloped and developing countries make an overall shift upwards while they solve their in-country problems.

Starting with in-country inclusiveness, the commitment to this form of social contract starts with governmental programs and policies and then ripples through to the private sector. In most of the developing world this should include inclusive and affordable access to quality health and educational programs. Educational access needs to include tertiary education and life long learning and skills development. There is also need for strong social services programs, for the retired, disadvantaged and those in-between jobs. There needs to be a continued movement from minimum wage to living wage programs and clear policies for Gig economy workers. Finally, ubiquitous equivalent access to the internet for all, through mobile devices such as smart phones, is one of the vital components to help move towards equality of opportunity. Financing of these programs can come in different forms including a proper approach to progressive taxes and taxes on wealth.

Small and medium businesses are vital for employment levels. SMEs (small and medium sized enterprises) comprise 60-70% of jobs in most OECD countries. They also provide a disproportionate number of new jobs creation. In the US, businesses with under 500 employees comprise 48% of all employees. Solving the failing of financial markets for small businesses is critical in a number of countries such as the UK. Governments should also be looking at providing a fair share of their sourcing and outsourcing expenditures to support small and medium sized businesses. It is a false economy for governments to focus disproportionate levels of their spend on large companies. In all of the developed economies, a significant portion of private company revenues is from procurement and outsourcing activities by governments at the federal, regional and local levels.

There are multiple examples of countries that have made progress across a range of the inclusiveness issues. There is the healthcare system in Singapore, Finland’s success in education, Scandinavia’s over all progress on gender equality, Denmark’s model of social security and mobility, and Switzerland’s strength on life-long learning. Of the larger countries, Japan and South Korea have very high scores on health and technology access and Germany is a strong performer in social protection and work opportunities. Good references for this are the WEF Global Social Mobility Report 2020, and R. James Brieding’s book “Too Small To Fail”.

Improving inclusivity and fairness in underdeveloped and developing countries is a big challenge. At the national level, countries must understand that consistent development support from the developed world is earned through strong political, economic, and social structures. Dictatorial behaviour and increasing concentration of wealth damages economic and social development.

Accelerated progress will only happen with external support. This includes foreign government policies on aid and assistance, financial support from intergovernmental organisations such as the IMF and Worldbank, and philanthropic assistance to tackle big problems such as what we are seeing by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

In the private sector, from multi-nationals there needs to be more rapid progress on progressing proper employment practices with fair pay, education and health support. In more remote locations, there is often also a need to engage more actively with the overall communities. Secondly, consideration should be given to special pricing, such as in the health sector, to increase the accessibility of critical goods and services. Finally, technology and innovation investment needs to be focused on solving both development and climate challenges. This includes ubiquitous access to clean water and sanitation, access to low cost continuous energy (ideally green energy) and quality internet access with smart devices. Social impact needs to be high on the corporate agenda as well as achieving a Net Zero carbon position.

Financing of the SDGs and in particular meeting the needs of the developing world is clearly a challenge. The UN Secretary General’s “Roadmap For Financing The 2030 Agenda For Sustainable Development” published in 2018, estimated a short coming of $2.5tn – $3 tn per annum to achieve the SDG’s in developing countries. This is against a context of global GDP being $88 tn and global wealth of about $215 tn. It is particularly challenging in the context of the need for post-Covid financial recovery and for the developed countries to set and meet their own climate and SDG goals. A majority of this financing will need to come from the private sector.

To achieve this, new financial thinking is required and alternative financing instruments are needed to improve the flow of finance to these needs. The current global situation of climate warming and increasing stakeholder response to inequities is changing the context of investment decisions creating the need to incorporate related economic and risk factors into long term financing decisions.

Global, national and local policies and programs drive change and where there is large scale change there will be broad sets of investment opportunities. The higher the level of clear and certain policy directions the bigger the opportunities in the private sector. Uncertainty is the enemy of growth and investment.

Increasing transparency on the risk and return of not engaging in driving impact will be a vital contributor to shifting investments towards solving these social and environmental challenges we are facing. The increasing requirements for ESG reporting and the movement towards consistent, comparable and auditable measurements will help embed impact into business decision making. However, what is also needed is growing stakeholder pressure to accelerate the incorporation of impact into strategies and business models. Consumers and employees need to help business leaders see that without impact their businesses will not flourish and be leaders in their markets. It needs to become clear that social and environmental leadership can be vital components of competitive advantage.

In addition, the potential of existing and emerging technologies to solve large global issues is real. There is no reason that this should not attract significant investment. Passionate impact oriented entrepreneurs with the latest technological know how have massive opportunities to create great businesses. Probably the most visible company in this space is Tesla which is focused on shifting the world to clean energy through electric cars, solar technology and battery storage. I am sure there is more to come from them. Other opportunities include the creation of low cost clean energy solutions for remote communities. Slingshot and Skysource are great examples of companies working to improve the availability of low cost clean water. Zipline, the leader in drone medical deliveries, developed their business in Rwanda where there was a critical need for remote and timely delivery of critical medical supplies. Elon Musk, Facebook and Jeff Bezos are all looking at building large satellite networks that have the potential to vastly improve internet access in remote areas. The business opportunities are immense.

There is already a $31 tn ESG and impact investment pool, which is about 15% of global investable assets. This level of money is already increasing the focus on companies that are creating impact as well providing shareholder returns; although, many of the companies in the pools are focusing primarily on ESG reporting first and only just starting on the journey towards to Net Zero carbon emissions and social impact.

New forms of financing at scale are also essential to contribute to filling the financing gap. The term used for the specific new forms of financing focused on generating impact is impact investing. Impact investment financial solutions work on the basis of risk-return-impact equations. A key proponent of this is Sir Ronald Cohen who has recently published a book talking about this, “IMPACT – Reshaping Capitalism To Drive Real Change”. Sir Ronald Cohen is a preeminent international philanthropist, venture capitalist, private equity investor, and social innovator.

The market for impact focused investment products is small today; but, it is emerging. Green bonds in the market today are valued at about $750 bn. These green bonds are being followed by blue (ocean), education, social and gender bonds. The DIB/SIB (Development and Social Impact Bonds) market will become more substantial through the scaling of Outcome funds. To achieve scale this will require some of the growth coming from the $5 tn investment pool comprising private equity, venture capital, real estate and infrastructure investing.

We understand the challenges of inclusivity and fairness. Through the UN SDGs there is global recognition of what needs to be done. It is now up to political commitment coupled with supporting governmental policies and programs, philanthropic support, and most importantly, private sector commitment to move towards risk-return-impact business models and investment criteria.

My next blog will cover the third challenge of ‘digital privacy and collective truth’. This is an emerging and critical challenge that unaddressed affects the conduct of democracies, the level of social instability across all countries, and the violation of the rights of individuals.